I was squatting by a roadside pull-off in Montana, gently combing my fingers through straw left behind by horse trailers, when I suddenly laughed out loud at the absurd situation I’d gotten myself into. I was literally looking for a needle in a haystack. Moments earlier I’d been disassembling the carburetor on my motorcycle, removing a tiny spring clip to adjust the mixture of fuel and air, and the precision needle inside had gone flying out of my fingers and into the straw. I felt like a fool for opening the damn thing on the side of the road but there hadn’t been much choice. The engine’s performance was getting worse and worse1 and I’d been compensating by fine-tuning the carburetor, but by then there was barely enough compression to start and the engine was only happy when it was running hot and fast. If I didn’t find that needle it wouldn’t be running at all. I felt an urge to kick the straw and stomp off.

“You need to get frustrated and learn to sit with it,” my therapist had told me in one of our last sessions. And then a few months later I’d signed myself up for an endless series of frustrations, attempting to ride coast to coast and back on a tiny motorcycle built in the late 60’s, rescued from the county dump and fitted with a cheap Chinese engine. The real obstacle wasn’t just the rust and the wear and tear, but my almost total ignorance about combustion engines. Carbs and chokes, rings and valves, cams and tappets, they’d all been just words to me and now they were little pieces of metal rattling around a hundred times per second, each of which could seemingly stop me in my tracks if it got bent, broken, or clogged with a speck of dirt.2 And by far the most likely reason for them to break was because of me doing something clumsy or stupid. It was hard to think of a better way to follow my therapist’s instructions. Stranded on the side of some back road, sweating my way through a frustrating repair, as much as I felt like stomping off, I’d eventually have to come back and carry on with whatever daylight was left. There wasn’t much choice but to sit with it.

I knew the mindset that I was supposed to be in. Robert Persig describes it in his classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, quoting a manual as saying “assembly of Japanese bicycle require great peace of mind.” The translated phrasing is cute and it’s good advice too, but how to get there? Persig never really explains it. I try to do something, I come up against an obstacle, and the frustration hits in a flood of thoughts: can I even do this, clearly I suck at this, so-and-so could’ve solved this easily, and then come the exit strategies of self-protection: this isn’t worth the trouble, this is kind of a dumb thing to be doing in the first place, maybe this isn’t what I’m meant to do. I had no idea how to get these thoughts to go away, and so the temptation was always to do something else, something that already came easy to me. But I also knew that was the path of staleness, of never learning or growing up. Maybe that’s why I’d gotten myself into this situation.

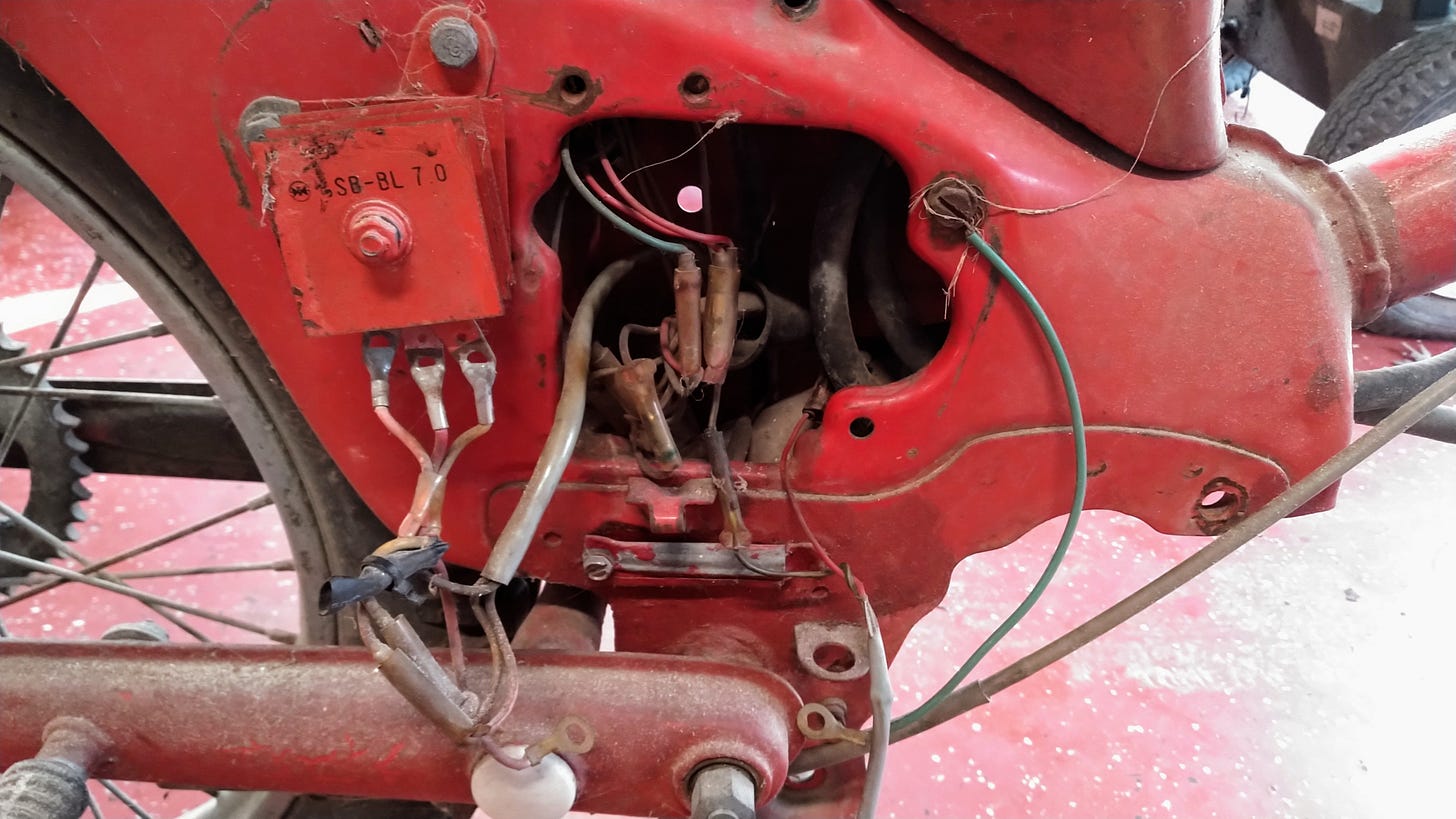

I wish I could say that there was some moment on that roadside in Montana, some epiphany that freed me from my frustration, but it didn’t work like that. I did what I had to do, I combed the straw for that needle and I found it, I carefully re-assembled the carburetor, started the engine, and rode to my next camping spot. And then I did the whole thing over and over again in countless forms: fixing a brake lever after slipping in gravel in Idaho, taking half the engine off in Nevada, replacing a melted battery at an Apache gas station in Arizona, changing and patching tubes on the side of interstates and suburban streets. Most dramatically I ran over a screw and crashed at full speed, stranding me at a closed interstate rest area, where I beat my fender straight with a rock and tried over and over to get one of my tubes to hold air.

Trying to patch those tubes, I made nearly every mistake there was to make, and eventually I ran out of patches and daylight. As the sun went down I camped in a gully between the off-ramp and the highway, trucks whooshing by on both sides and a storm rolling in with predictions of 55 mph winds, hail, and torrential rains that threatened to flood me out. Exhausted, hopeless, and a little scared, I called a wise friend for support, and she reminded me that the material journey I was on was nothing in comparison to the spiritual one. It wasn’t about a motorcycle or a road or a destination, it was about learning to love myself through all of these mistakes and mishaps.

And in that moment, loving myself meant letting myself be held and carried. Dogged persistence had gotten me that far but it wasn’t going to get me any farther, it was time to let myself be helped by outside forces. I had called a friend and felt better. As if by a miracle, the storm parted and passed on either side of me, leaving the gully dry. The next day I paid a tow-truck driver to take me a hundred miles to Phoenix where I could rest and buy parts. The journey continued. I had failed, and yet I hadn’t failed.

In North Florida, some 9,000 miles into the trip, my second engine was starting to give out like the first, and again I had my carburetor in pieces, spread out on a blue tarp in a campground. This was the final leg of the journey, and I knew that if I damaged or lost a part, I might not be able to join my family for Thanksgiving. At first I felt anxious, but I had my friend Phil behind me, never touching a wrench but just projecting calm. And his calm was grounded in real knowledge: he was a skilled mechanic with countless repairs under his belt; one time on a cross-country trip, he even swapped out the entire engine of his van under an oak tree by the side of the road, winning a bet with some locals in the process. “Ain’t no hurry,” he told me, “we got all day. Ain’t nobody gonna die.”

I was consulting a repair manual on my phone, but Phil, not being able to read well, had probably never read a repair manual in his life. Everything he knew, he learned by asking questions and making mistakes, and somehow I knew he wasn’t going to think any less of me if I did too. I began to relax, knowing I would get through this repair, and if I didn’t, that I would have spent the afternoon with a dear friend, and we’d probably have an adventure driving in his van to meet my family, and a good story to tell over turkey and cranberry sauce. The little pieces of metal spread out in front of me might be able to stop my motorcycle from running, but they couldn’t make me lose a friend. I could mess up a hundred repairs and nobody would love me any less.

I rarely feel frustrated anymore, and when I do it doesn’t last long. I think the shift was realizing that even when my frustration seemed to be directed at the outside world (why won’t this stupid thing work) it was really directed inward at me (why am I too stupid to make this thing work). With more self-love, the answer comes clear, and it’s almost always either because I haven’t learned how yet or because I need some help. When my beloved inner child struggles to climb the stairs or stretches to reach for a book on the top shelf, I can offer words of encouragement or call for someone taller to help out. If we want to learn, to grow wiser as well as older, we have no choice but to struggle and reach for things beyond our grasp, to encounter an endless series of obstacles, and to overcome them by loving ourselves even in our ignorance and weakness. May we all have the courage to continue into wisdom and strength.

P.S. I want to send a special thanks to my friends Ray and Meredith, whose warm hospitality was a blessing in that cold, wet, and discouraging winter of 2020/2021. My journey started and ended at Ray’s garage in the woods, with its little altar to Ganesha the remover of obstacles. For me it’s like a temple of patient and curious persistence, with Ray as its chief priest. I tried to learn his calm by working beside him, but I am hardheaded and in the end I had to ride in a 10,000 mile circle around America and come back changed.

This was definitely my fault, such engines are designed for riding around on dirt trails, not touring at full throttle all day, which is what I was doing.

A really great insight in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance is that one stripped screw can stop a motorcycle from running, and until this is fixed the motorcycle is, in some important sense, not a motorcycle. Nothing drives this feeling home more viscerally than being far from inhabited places with that motorcycle as your only form of transport. This fragile quality of technological objects is part of what made me switch to walking, as I talked about here.

Jesse, this is one of my favorite pieces of your writing. And reminds me of the aphorism, "Hard times make strong people. Strong people make easy times. Easy times make weak people. Weak people make hard times." So I celebrate with you that you rarely feel frustrated, or at least you don't feel frustrated for overly long. You have learned to sit with your frustration, a likely with thorny emotions as well. This is so helpful in hard times. And I hold the vision that you are creating space in the collection consciousness for others to learn to "sit with" hard times until they can return to quiet and listen for and ask for help, from other people, from one's deeper self, and from the divine. Thanks for this beautiful example from your own life.

Wow, what a great account to read !